Even veteran attorneys like Benjamin Crump describe getting police body camera footage as “daunting.”

When Ronald Greene died at the hands of police, body cam footage was never meant to be seen.

In May 2019, troopers stopped Greene for a traffic violation near Monroe, Louisiana, and at the time, said the 49-year-old Black man fled and resisted arrest.

Lt. John Clary of the Lousiana State Police arrived at the scene moments after troopers physically restrained Greene by punching and stunning him. But Clary denied to investigators that there was body camera footage of Greene’s arrest. John Peters, another state trooper present during Greene’s final moments, allegedly issued the following warning, according to a judge on the case:

“Don’t send the videos unless the [DA] asks for it.”

The public remained unaware of the videos for two years until the Associated Press obtained and published them.

Body camera footage has long been touted as an essential accountability tool in police reform. From Louisiana to Tennessee to Wisconsin, there have been high-profile cases of Black people harmed, mistreated, or killed at the hands of police, where body camera footage was withheld from the public.

“It has been daunting,” renowned civil rights attorney Benjamin Crump said in an interview with theGrio. “It’s very difficult in most states to get video released. They hide behind these oppressive laws that say, ‘Well until we finish the criminal investigation, we won’t release the video.’ And then they just string along the investigation for months, sometimes years. By the time they release the video, everybody’s swept your loved one under the rug.”

Crump noted the negative impact these delays have on Black families.

“It’s heartbreaking because the family knows that there’s evidence out there that would tell us truthfully what happened to my son or what happened to my daughter, to my loved one,” Crump told theGrio, who compared Greene’s death to the killings of George Floyd and Tyre Nichols. “But they hide behind these technical legal legalities to never release that video until you feel worn down and just defeated.”

Body-camera footage published by the Associated Press shows that state troopers beat, tased, and pepper-sprayed Greene, pulling him out of his car, dragging him by his ankles, leaving him with blood pouring out of his head onto his brown forehead, staining his green T-shirt.

“I’m scared!” Greene screams on video not long before he eventually slumps with his hands handcuffed behind his back. When Clary, the highest-ranking officer on the scene, first arrived, another officer signaled that the lieutenant’s body-worn camera was filming, resulting in Clary shutting it off. According to documents reviewed by CBS News, as Greene’s head slumped, troopers didn’t make efforts to reposition his head to ensure he could breathe clearly for six minutes. Parademics testified that Green was dead when they arrived.

Allegations of a police coverup only gained steam once the body camera footage was compared with what police say happened.

“The official story was that he ran into a tree and died. But what happened when body camera footage came out? We know that a number of officers gratuitously beat this man to his death,” said Nora Ahmed, legal director of Justice Lab, an initiative of the ACLU of Louisiana, which seeks to end racist policing. From Ahmed’s perspective as an attorney, body camera footage that goes viral or gets amplified in the news media can change everything.

“I want to believe that the Department of Justice would be investigating the Louisiana State Police today in the absence of body camera footage. But I do not believe that would be the case if what happened to Ronald Greene did not hit national news,” she told theGrio.

But numerous challenges, from the timeliness of footage released to difficulty in getting the police to release footage based on individual state and department rules, reveal that police body-worn cameras are not always ensuring justice for families when they need them most.

Cameras everywhere, footage hard to get

According to the Bureau of Justice Statistics (BJS), as of November 2018, only 47 percent of general-purpose police departments had body-worn cameras, while in large police departments, the number was 80 percent.

Although President Joe Biden mandated body-worn cameras for all federal police agencies through a historic executive order, it is up to states and individual police departments to implement their body camera policies. Should a new president step into the White House, Biden’s body-camera mandate could be undone.

“I believe the police almost always benefit when there’s greater transparency,” said Bob Harrison, an adjunct researcher with the RAND corporation whose 30-year police career includes a stint as police chief in Vacaville, California.

Despite his general support for cameras and recording devices, Harrison said body cameras present numerous problems for police departments.

Harrison said officers must learn to make turning on their cameras second nature, just like grabbing a flashlight when they step out of the vehicle. Once the footage is captured, then departments must be equipped to manage it.

“I think people don’t realize how much time it takes to review, redact, and prepare body cam footage,” Harrison said. “The time it takes to manage that is a personnel time consumption. It’s a really complex process.”

Harrison cites storage as a problem. One eight-hour shift of police body camera footage balloons quickly when multiplied by five days a week, four weeks a month, 12 months a year, and hundreds of officers in one department.

Police departments without proper storage systems or personnel to manage FOIA requests may become quickly inundated. TheGrio’s efforts to obtain body camera footage from multiple police departments took months, with some departments seeking to charge hundreds of dollars in fees or declining requests. One department in Flordia charged approximately $300 for five police body camera cases. A department in Louisiana said the request for body camera footage caused an “unreasonable burden” and could not be fulfilled.

Another factor that can delay the release of body-worn camera footage is privacy concerns.

When a Black Georgia couple was stopped by police in Tennesee, resulting in their five children being taken away and put into foster care, a judge denied the release of police body camera footage to the public. Coffee County District Attorney Marcus Simmons cited privacy concerns for the children, who were 4 months to 7 years old at the time of the incident. The parents have an unredacted copy of the video, according to the Tennessee Lookout.

The Lookout reported that Simmons instructed the parents to file a records request via the Tennessee Highway Patrol, allowing the department to redact what they choose.

“I am sympathetic to the privacy argument but… you also trade a little bit of privacy when you voluntarily serve in a taxpayer and public-funded position,” says Jon McCray Jones, a policy analyst with the ACLU of Wisconsin.

In Milwaukee, McCray Jones cited a case where a Milwaukee civilian oversight board asked that police release body camera footage within 15 days when someone dies or is injured at the hands of police. But Milwaukee’s police union sued over the policy and successfully stopped it, for now.

“The reason why police unions and a lot of police departments want to hide this transparency is because it’s not to protect the public. It’s to protect each other,” McCray Jones told theGrio.

He also said police pushback around the quick turnaround of body camera footage is strategic.

“The longer that cops control body cam footage, it allows the cops to create a story, review the evidence, find certain things in the footage, they can help paint themselves in a better [light],” McCray Jones said. “It also allows the department’s PR teams to sit there and control the narrative.”

“The longer that the police are able to hold that video footage, the more likely it is for public outrage to die down,” McCray Jones continued. “People have bills. They have kids to feed. And with the 24-hour news cycle, they also have other issues that they need to care about.”

In Washington, D.C., Mayor Muriel Bowser recently rolled back several police reforms in the wake of spiking crime amid concerns about their effectiveness.

One rollback included removing a policy that prevented officers from reviewing body camera footage before writing a police report — a move that RAND’s Harrison agrees with.

“I think that’s a good thing because it saves time and energy for cops who can then get back out in the field and respond to calls,” Harrison told theGrio. “I think we’re probably moving towards the nominal elimination of written police reports; a well-narrated body camera footage with supporting documentation can become the police report.”

A fight that can involve the courts

For the families and lawyers on a quest for justice for their loved ones, sometimes the fight to get access to body camera footage has to go to court.

“We filed public record lawsuits, Freedom of Information Act, Sunshine Law, lawsuits constantly,” Crump explains. “But regrettably, most state supreme courts and most state legislatures have sided with police unions to block access to transparency.”

Organizations such as Justice Lab in Louisiana are also taking legal action to sue for access to footage despite claims that police investigations are “ongoing.”

In the case of 18-year-old Calvin Cains III, who was shot to death by deputies from the Jefferson Parish Sheriff’s Department — the same department where his mother, Mallory Cains, worked for years— police won’t release footage due to the investigation, and his mother has sued.

“There is still this belief that police violence against Black people is an aberration,” Justice Lab’s Ahmed said. “It will take actual, unfortunately, documentary evidence for people to stop thinking that it is an aberration and to start understanding that the problem that we have is systemic.”

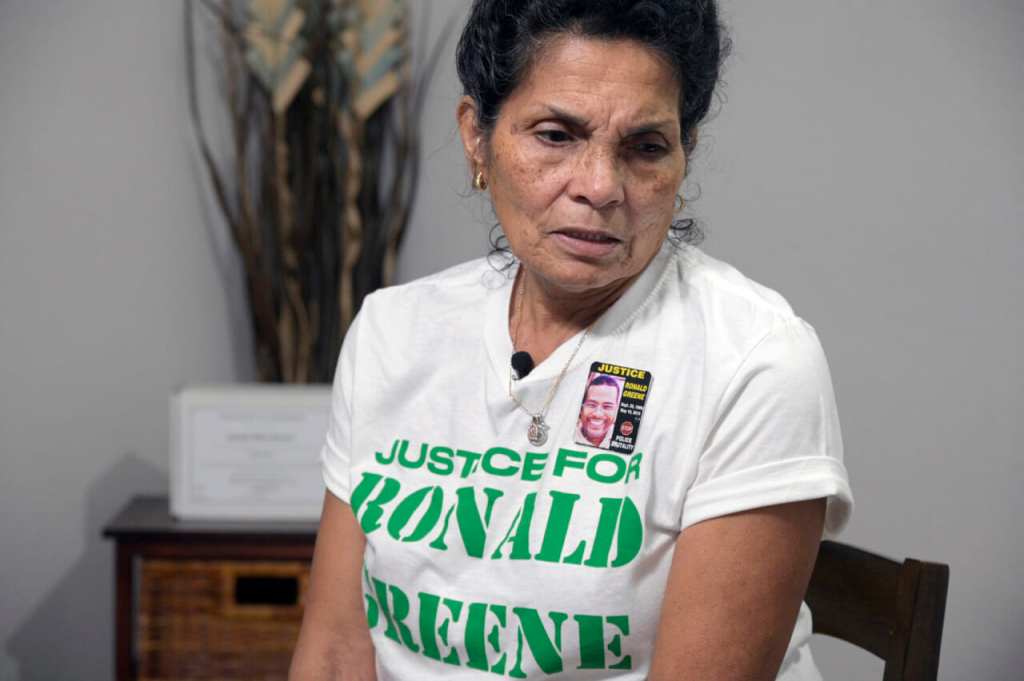

In the case of Ronald Greene, his family’s fight still plays out in court.

Six officers were on the scene that day: Dakota DeMoss, John Peters, Kory York, Chris Harpin, Chris Hollingsworth, and Lt. John Clary.

Hollingsworth died in a car crash a year after Greene’s death upon learning that he would be fired over the incident. DeMoss faced malfeasance and obstruction-of-justice charges for turning off his body camera during the incident, but a judge dismissed the charges.

Peters, the commander who the court said allegedly told officers to “bury” body camera videos and not let the DA see them, also had his obstruction of justice charges dismissed.

Harpin faces malfeasance charges in connection with the Greene case.

Last month, a judge dropped charges of malfeasance and obstruction of justice against Clary in exchange for his cooperating with the case against York.

York has been charged with negligent homicide in connection with Greene’s death, a charge upheld by a judge, which Greene’s mother, Mona Hardin, said “lifted” her heavy heart, The Associated Press reported.

For policy analysts like McCray Jones, the change he hopes for extends beyond one case and is one that would benefit civilians and cops alike.

“In a perfect world, I think that we need to embrace [the idea that] body cameras help everybody,” McCray Jones said. “Forty-eight hours is the perfect scenario. That’s morally the minimum that we can do is give the family access to the police within 48 hours. The public [and media] should have access to those within five business days.”

Even with these policy recommendations and legal efforts, the fact remains that body-worn cameras are merely a tool in the effort to improve policing for all.

Bob Harrison, who once took the initiative to hand out audio recorders to his police officers long before body-worn cameras became more commonplace, said he believes communities benefit when cameras catch good behavior too. Ultimately, Harrison said, the enduring change will come from officers:

“Culture transcends law.”

Additional research and support for this reporting series on body cameras was provided by: Eric Sagara, Dana Amihere, Dilcia Mercedes, Lisa Seyton, Irene Casado Sanchez, Lisa Pickoff White, Ananya Tiwari and Lindsay Walker.

This article was reported in partnership with Big Local News at Stanford University. The series was funded by a grant from the Pulitzer Center for Crisis Reporting.

Never miss a beat: Get our daily stories straight to your inbox with theGrio’s newsletter.

The post Body cameras were supposed to hold police accountable – but getting footage is harder than you think appeared first on TheGrio.

New Comments