One evening in January 2018, the police were called three times by workers from the Kent office of the Washington Department of Children Youth and Families (DCYF). The reason behind the call was because of an out of control 11-year-old girl in the foster system.

In recent years, hundreds of children similar to the foster child are being placed in hotels because no foster families or group homes would take them. According to state records, the child was awaiting counseling for sexual abuse and wasn’t allowed to be left unsupervised with children more than two years younger than her. The month before the incident the girl had assaulted three workers while they supervised her overnight in a hotel. The night the cops were called, according to state documents that were obtained by InvestigateWest, the girl was obligated to stay at the Kent office because she couldn’t be safely transported to a hotel. A month later, the girl’s behavior escalated after cycling from hospital and hotels. After about seven weeks of instability, the girl was finally placed in a program for troubled foster youth with behaviors that numerous foster parents find too hard to manage.

The girl is one of many children who are placed in hotels and state offices sometimes on and off for weeks or months. The foster systems are struggling to build services where they foster those suffering from significant mental health and behavioral challenges. A recent report by the Washington Office of the Family and Children’s Ombuds shows that there was a 39% rise of hotel stays then the previous years and its the highest since Ombuds began tracking them five years ago. According to the DCYF, the state has too little group home spaces for those who need intensive treatment. Because of the shortage of in-state options, it leads the state to ship many of the hard to place foster children to out-of-state group homes, some of which were criticized for mistreating kids. The state is working on bringing all the foster youth to Washington, where they can easily monitor them but this process has been hindered because of lack of in-state group homes qualified for severely troubled youth.

Dee Wilson, a former regional administrator in Washington’s child welfare system who now trains social workers, voiced his opinion in light of low funding. “This is ‘chickens come home to roost’ for bad public policy and inadequate funding of both child welfare and public mental health during the past 10 to 15 years or longer.” Legislators in Olympia are trying to approve the second half of the two-year budget and critics say that if Governor Jay Inslee has it his way the foster system will continue to fall short.

Hotel Stays

The Ombuds reports say, the effects of children in the foster system staying in hotels are suicidal gestures and attempts, increased sexual assaults, increased fires in state offices, and multiple arrests. Most of these foster kids spend the majority of their time in DCYF offices instead of going to school and their diet consists of fast food. These children living in these conditions often feel like no one wants them and that they are unlovable.

Earlier this month, Ombuds Director Patrick Dowd told the DCYF oversight board that this experience is “another level of trauma being inflicted on these children”.

To address the issue at hand, Governor Jay Inslee has issued a 2020-21 supplemental budget that includes $7.6 million for 33 long and short-term beds in facilities with therapeutic services for children who suffered from acute mental health, developmental, and behavioral needs. Various Democratic lawmakers say the governor’s proposal will fall short because the state had to move 26 of those foster youth out of the children’s mental health agency Ryther. The Seattle nonprofit said they won’t be able to help foster youth at the reimbursement rate the state was offering.

The DCYF spends about $2,100 per night for a hotel stay, most the costs include two social workers and a security guard who would have to stay up all night to watch over a child. These hotel costs are about five times the $422 per night the state pays for in-group homes. Since 2015, hotel stays have been costing taxpayers an estimated $9.3 million.

Kids With Mental Illness

According to records that were obtained by InvestigateWest, examples of children that are placed in hotels and offices are:

- 17-year-old who functions at the level of a three to four-year-old.

- 11-year-old who displays sexualized behavior and can’t be around small children.

- Seven-year-old that displays significant disruptive behaviors, which can include destruction of property and assault of staff and caregivers.

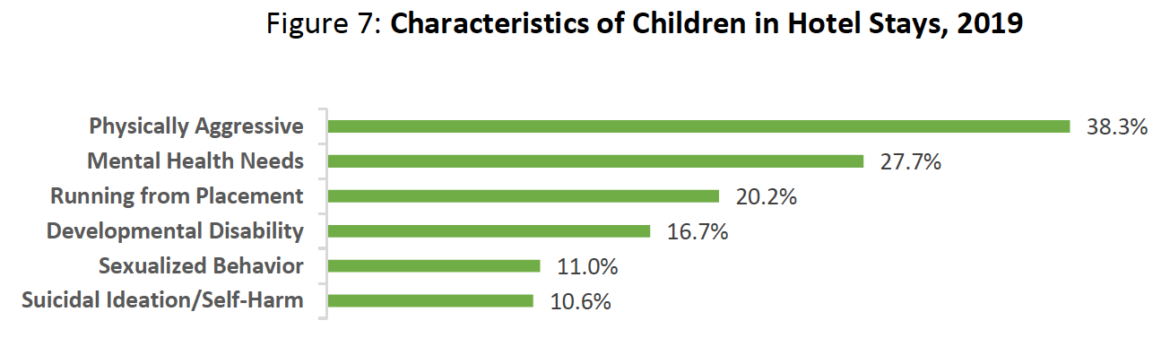

Many of these cases have been diagnosed with and hospitalized for various mental health conditions. More than 38% of these children in hotels last year had a history of being aggressive and 28% of these children needed mental health treatment. Other common behaviors would include running away, developmental disabilities, sexualized behaviors, and self-harm.

(Source: Washington State Office of the Family and Children’s Ombuds)

Multiple Night Stays In Hotels

About 40% of the children who stayed in the hotels last year only spent a night there, while they were transitioning between foster homes. About 40 kids accounted for more than half of the hotel stays, while a dozen kids spent 20 or more nights in the hotels. One child spent about 77 nights in the hotel. Social workers mentioned that certain programs in the state that are meant to control or handle these children are kicking them out or turning them away. These programs include group homes and specially trained foster homes, and DCYF’s Behavior Rehabilitation Services (BRS) which provides help for those suffering from behavioral and mental health challenges.

Wilson, who was a child welfare veteran and has reviewed about 100 social worker reports on hotel stays by InvestigateWest’s request said, “Very few BRS programs will take youth who require two or three-line staff and a security guard to manage them overnight”. Because of these reports, Wilson said that many of these cases need intensive residential mental health treatment in the Children’s Long-Term Inpatient Program (CLIP). But because of the state’s growing population, CLIP hasn’t been kept up. DCYF is requesting Governor Inslee to add at least 10 CLIP beds to foster youth on top of the 84 they currently have. This request was not included in Inslee’s proposal to the Legislature.

Today, the number of out of state foster kids are down from 100 to 31. Although it places “greater demands on existing placements resources,” Secretary Ross Hunter doesn’t think there is a connection between more kids being sent to hotels because fewer are being sent out of state. “If that were the case, I would go back to putting them out of state, because I think it’s better for kids to be in a stable placement, rather than being in a hotel or an office stay, even if that placement is out of state.”

According to Ombuds, some hotel stays that are under DCYF regions would cover the costs of King, Whatcom, Skagit, and Snohomish counties. While in other parts of the states many social workers are relying on night-to-night stays in foster homes in which they will keep the child from bedtime until breakfast. According to reports, many of these stays are costing taxpayers $600 a night. Hunter doesn’t agree with this system at all. He says although this tactic is convenient for certain places it is emotionally damaging to the child because it is showing them there is no place for them.

Assaults On Staff

According to Ombuds’ report, children assaulting staff members in hotels isn’t uncommon. Because of that neither the Ombuds or DCYF tracks how often assaults occur.

In November 2018, a six-year-old foster child that was staying in the hotel punched a social worker in the face and threw a cup of coffee at her. The same boy threw a water bottle at another employee which hit her in the face. In addition to attacking the staff members, the boy broke two lamps. The workers eventually called the police who then took the child to the hospital for mental health observation.

Staying in hotels and offices can have a “dysregulating effect” on the youth, especially to those who suffer from mental health issues. It can also contribute to criminal behavior.

Unlike staff members in group homes, state social workers lack the training to control extreme behaviors which many of these children exhibit. Because of this, many of the after-hours workers who supervise kids are almost always least experienced. Although they lacked experience, the only thing these workers can and do often use against the violent child is physical holds. Because this job is stressful and often times dangerous, it can contribute to a high turnover rate.

Child Welfare

Not all children that are staying in these hotels are removed from their parent’s care because of neglect and abuse. In most cases, some parents are overwhelmed by their child or children’s needs and they felt unable to care for them. Because many parents refused to pick their child up after they’ve been discharged from the hospital or from juvenile detention, it can prompt social workers to call Child Protective Services. There is an increase of children who suffer from developmental delays winding up in the system’s care. Because of the recession, there have been cuts to community mental health resources and services.

Hunter said because of the lack of resources, DCYF has become the last resort. He said that he is working with leaders from the Health Care Authority and Developmental Disabilities Administration to find solutions.

A Search For Solutions

Washington, like most states, has struggled to attract and keep enough foster parents. The most challenging part is not the many children living in the hotel and trying to recruit foster parents but the children’s behavior towards the property, and being overly sexual.

DCYF regional administrators suggest the best way to make the transition smoother for the child and the family is by offering a class for professional therapeutic foster parents who are trained and paid full-time to care for high-needs kids. Wilson agrees saying, “the only good alternative to residential care currently is professional foster care. “Based on Wilson’s review of DCYF, he estimates that about half of children could be cared for by professional foster parents.

Earlier this month at a meeting with the DCYF Oversight Board, former Washington Supreme Court Justice Bobbe Bridge told her colleagues it was time for the state to revisit the idea of professional foster parents. She also said the state should increase short-term receiving foster homes that way they can keep the bedroom available for children in emergencies. This is part of DCYF’s original budget request which will cost $3.3 million annually. The department will also ask for $721,000 for workers and services which isn’t included in the budget.

Wilson called the budget “a pathetic, token response to the state’s foster care crisis”. He also added it’s intent was to keep things business as usual. Last Wednesday, Inslee’s office issued a statement saying, “Funding to increase the number of placements for youth who need more intensive behavioral supports is an important first step to eliminating the need for hotel stays.” The statement didn’t provide a specific plan but will provide additional strategies in the future.

Last year the legislature found an additional $38 million that the state pays to Behavior Rehabilitation Service group homes before the Great Recession. The reason behind the findings was to stop a decade-long decline in those services which the department says has contributed to kids staying in hotels and out-of-state placements.

According to Hunter, the new higher BRS rates went into effect last fall and he expects the agencies will open more beds to the children. But agencies in the Seattle area said that even with the new rate this won’t account for the region’s higher minimum wage and cost of living. CEO Karen Brady felt that Ryther the residential program would have cost about $1.2 million because of the new rate. But they decided it no longer do business with the state. Another program that stopped accepting children in 2017 was Navos. Western Washington lost about 41 long-term Behavior Rehabilitation Services. According to providers, this leaves about 10 BRS group home slots in Seattle.

Hunter said he hopes that the governor’s proposal for the 21 long-term “enhanced” Behavior Rehabilitation Services bed and will help get big companies like Ryther back. He also said that he would want to rely less on group homes, although that’s not possible. Child advocates say that children in foster care would do better in family settings.

Washington already places a smaller proportion of foster kids in group settings than the national average.